Although he came out with one of the most exciting albums of recent times with his band: Zoord they are less known in Hungary than in Yakutia or Japan. He is more inspired by undiscovered paths than the mainstream, which he considers to be dull. Áron Szilágyi is not only a member of the band Zoord but he is also in charge of The Leskowsky Musical Instrument Collection in Kecskemét. We asked him about following his father’s footsteps, the Mouth harp, the ever so open and welcoming Yakutia where during the winter it can get as cold as -30 degrees Celsius and where punk is definitely not dead, about the music of Moldva, creating communities and about the best musical instrument collection of Hungary where old instruments are not mere dusty objects to be observed by visitors.

So, you were born with a Mouth harp in your mouth.

I was born together with the Mouth harp as my father (Zoltan Szilagyi) just about started making Mouth harps when I came to this world.

What did he do before that?

He was a librarian and a poet. Here in Kecskemet people know him to be a poet but in fact he painted as well. He had a lot of friends from Szentendre (Waszlavik, feLugossy, etc.) which was a kind of a Mecca of artists at the time. My dad used to tell us about how they had been utterly aimless and absolutely wound up by everything at the same time and how they had reckoned that all of them should be mentioned in an encyclopedia one day. Well, one has to admit that this very last goal was fulfilled in all of their lives: some became well known artists, one is a mathematician, and there’s the Mouth harp maker as well, of course.

How did he start making Mouth harps?

Out of the blue, basically. He says he had spiritual guidance in finding this profession. One day he heard a Mouth harp being played on the radio and so he wanted to make a device that can deliver the same sound. Of course he had never seen such an instrument before. His first instrument looked like a fork and was made from an actual fork, a piece of bicycle chain and an umbrella reed. He still has this, actually. After this first attempt he tried using nails, he was desperately searching for the perfect device that could deliver the perfect sound. Our flat was full of these experimental instruments, there were thousands of them in fact. And then in 1978 a Dutch couple visited us and the wife recognized the Mouth harp: she became his first customer. So this is how my dad started to sell his Mouth harps. In the beginning he attended fairs but at around this time the so called ’folk dance movement’ became very popular in Hungary too so he could sell at these gatherings as well. This movement inspired people to be more open and to experiment with traditional values. Musicians were very happy for him as back then the only Mouth harps available came from Austria and were of very poor quality. Those were factory produced instruments and my dad had hand made, crafted ones, so very soon the major Hungarian toy distributor started ordering from him instead of the Austrian manufacturer.

Your father is considered to be one of the best Mouth harp makers in the world.

Well, he certainly is one of the most well known to be sure. Judging an instrument is always very subjective. I think that he might be the best Mouth harp maker in the world because he can make many different types of instruments that fulfill different musical demands.

Let’s talk a bit about the instrument and its history to begin with.

The Mouth harp is an extremely primitive instrument and that is not an understatement. It comprises of two parts: a frame and a spring. Since this is such a simple device the slightest alteration can modify its sound completely. The first prototypes were made of bamboo, in fact in South-East Asia they still use this as a basic Mouth harp building material. Some others have been made of wood or fishbone too but these are not suitable to play West European music as they cannot play overtones accurately enough and they cannot play rhythm or tune unlike the ones that are made of metal. You can find some instructions about how to use them here.

What kind of metal are they made of?

Most typically they’re made of steel but in Yakutlia for example all sorts of metallic raw materials are used from around the house like saw blade or else. Up to a certain level it doesn’t really matter what you use as long as you’re an expert Mouth harp maker. My dad’s instruments are made of a special kind of steel that is produced in the steel factory. That is the frame only, as the spring is made of yet another material- a special alloy made of 16 different ingredients my father selected. All instruments are different in sound and style, some more aggressive, some more playful. You can find everything about Mouth harps here.

The sound of the Mouth harps is exquisite, genuine and mysterious. What feeling does it convey?

The sound of the Mouth harp triggers an ancient feeling in us. This is a very humane instrument as it does not produce sounds by itself, only in our mouths. It is also special as the player hears a completely different sound than the listener our ears and pharynx being connected. One cannot play out of tune on a Mouth harp as all its sounds are harmonious. Only the natural overtone scale is audible, all the sounds are in harmony with the do. Whatever you play will sound natural and enjoyable. This is exactly why so many people like to play it: they can deliver instant gratification regardless of who you are or where you are from. The sound triggers the very same thing in all of us, maybe one cannot decode this sensation but it is there, within everyone. The Mouth harp is one of the most global and local instruments. I believe in the globalization of the Mouth harp.

What is this sensation of being the player and listener at the same time?

Well, it is not easy to explain this being involved in it as I am. There was this guy who came to one of our concerts some 10 years ago to a club and after the gig he sent us an email about how he felt during the show that reflects the issue pretty well. He wrote that he felt like he was getting rid of his human mask and turned into his wild, instinctive animal self and wanted to roll in his own sweat. Music impacted directly the bone marrow, skipping the brain, taking complete control over the body. Needless to say he was not under the effect of any drug or substance.

I would really like to experience this once but unfortunately I cannot overcome the situation I’m in as a player. Of course I can reach trans-like sates but only when I play for myself. During a concert I have to stay focused. Concerts provide a different kind of elevation: the experience of breathing together with the audience and playing music together takes us to a different state of mind.

Before the release of Zoord’s new CD you went to Yakutia. Why did you have to go so far with Csango folk music in order to put together the album?

The story goes way back: in Yakutia Mouth harps are so important and popular as the Opera is important in Italy. Since this is their national instrument they establish institutions on it and concerts are also very frequent. Their most famous folk musician, Albina Degtyareva performs in Carnegie Hall and The Royal Albert Hall with her Mouth harp.

I met the director of the Yakutsk Mouth harp Museum at a conference in Kiev and he was very eager to invite us to Yakutsk to show how we played our Hungarian Mouth harps. Of course we happily accepted the invitation but I had to explain that Hungarian Mouth harp folk music doesn’t exist and that only Csango music uses this instrument authentically. I also had to confess that I don’t really play authentic Mouth harp music myself as I use the Mouth harp as a solo instrument generating a much bigger volume of energy when I play. After a little hesitation he still agreed to invite us but since he paid for our travel and accomodation costs he insisted on us being his ’slaves’ as long as we stayed there. Of course we were very happy to accept the offer although Hungarians have some really nasty memories about Siberia and we only had one tiny request: we wanted to go to the country to experience the real Siberian everydays. We wanted to see places where Europeans don’t really go to and wanted to meet the people who live in isolated places in order to show them our music. So this is how we spent ten days in Yakutia travelling 2500 kms throughout the Taiga

First we had a few shows in Yakutsk, one of which was in the local opera house in front of an audience of 2500 people, broadcasted live on television. We were the biggest attraction there, our concerts were advertised everywhere, even the news programme had a commercial break to hype us. Weekly magazines published four page interviews with us and on our way home on the aeorplane passengers wanted to have their photos taken with us. The organisers were fantastic: we could play at such cool places like the 60th birthday of the president in the hall of their Parliament, in different schools, in the Opera House and in all sorts of cultural institutions. Eventually we could set off to the country, 800 kms away from Yakutsk by a bus that was designed to carry 8 people, nevertheless we were 14.

So what were the circumsatnces like?

When we were there they had a relatively mild weather so it was only -30 °C but the coldest place we visited it was -54 °C. The engines of the cars are never stopped, for they cannot be restarted again. Although in cars there is a heating system, on their buses there is a stove to heat with so it’s weird that your leghair gets burned while the windows are frosty. Houses are heated heavily: the average temperature inside is +25-27 °C normally but it can get very tough when it gets so cold that the heating system gets frozen. Since in such cold weather one can only stay outside for half an hour without getting frostbites most people get around in cars. If there is someone you meet in the street whose face is too blue you have to tell them to rub it. We played in such places you cannot even find on Googlemap. Regardless of age or sex everybody wore traditional clothes and they all danced to the Szerba while recording the rest of the show with the latest iPhones. We could barely sleep. We stayed up 48 hours after sleeping a couple of hours. Adrenalin kept us awake. We were so wound up, and we also had a blog we had to complete every day so as not to forget anything, so many things happened we had to note them down.

Have you met any local informants?

Of course, and with most of them we jammed as well. There is an authentic and a modern version of Yakut Mouth harp music. Many young people use techno music as a basis but it is also taught at school in traditional music lessons. Tradition is documented and is spread word of mouth. There are an awful lot of people who teach traditional music at schools. In the Yakutsk Museum of Mouth harps there are thousands of intstruments made by by local masters, they don’t really have any other traditional musical instrument apart from shaman drums perhaps.

One can learn a lot from the Yakuts. Yakutia is a very special place being the largest non independent republic in the world. Its size is over a million square meters, its population is one million, half of whom are Russian. Self determination is dominant. The government is supporting patriotic feelings in order to avoid getting the Yakuts in minority situation but it is not against the Russians at all.

They simply highlight their national values and hype them very well before exporting them. In case of the Mouth harp it works like you hear it all the time that they are the best at playing it and they have the best instruments, in fact it was their very nation who invented the Mouth harps in the first place. Of course only a little of this is true but if they repeat it enough they will eventually believe it. On a practical level it works like if there is a world music festival somewhere in the world then the Mouth harp players will be invited from their country and from Hungary for example. Their music programmes are financially supported by the government which covers their travel costs all over the world where they not only play their music but also sell their special Yakut Mouth harps.

How did they welcome you guys?

Everywhere we went the local mayors or the regional cultural leaders greeted us eagerly. We were invited so as to be informed about the positive features of their country i.e.: why it would be such a good idea to invest there, what different tax incentives and industrial parks are available and finally took their leave hoping to meet us again soon. They probably figured that although we are just mere musicians from a country half the size of one of their county, we might very well take the news of their business opportunities to all our aquaintances in Hungary among whom there might be some who would be interested in such things.

In Viljujszk we met the major to whom I gave a book about Kecskemét on the cover of which there was a church. On taking it into his hands he immedately claimed that the only catholic church of their country is in their town and organised a little visit there, inviting the local priest too.

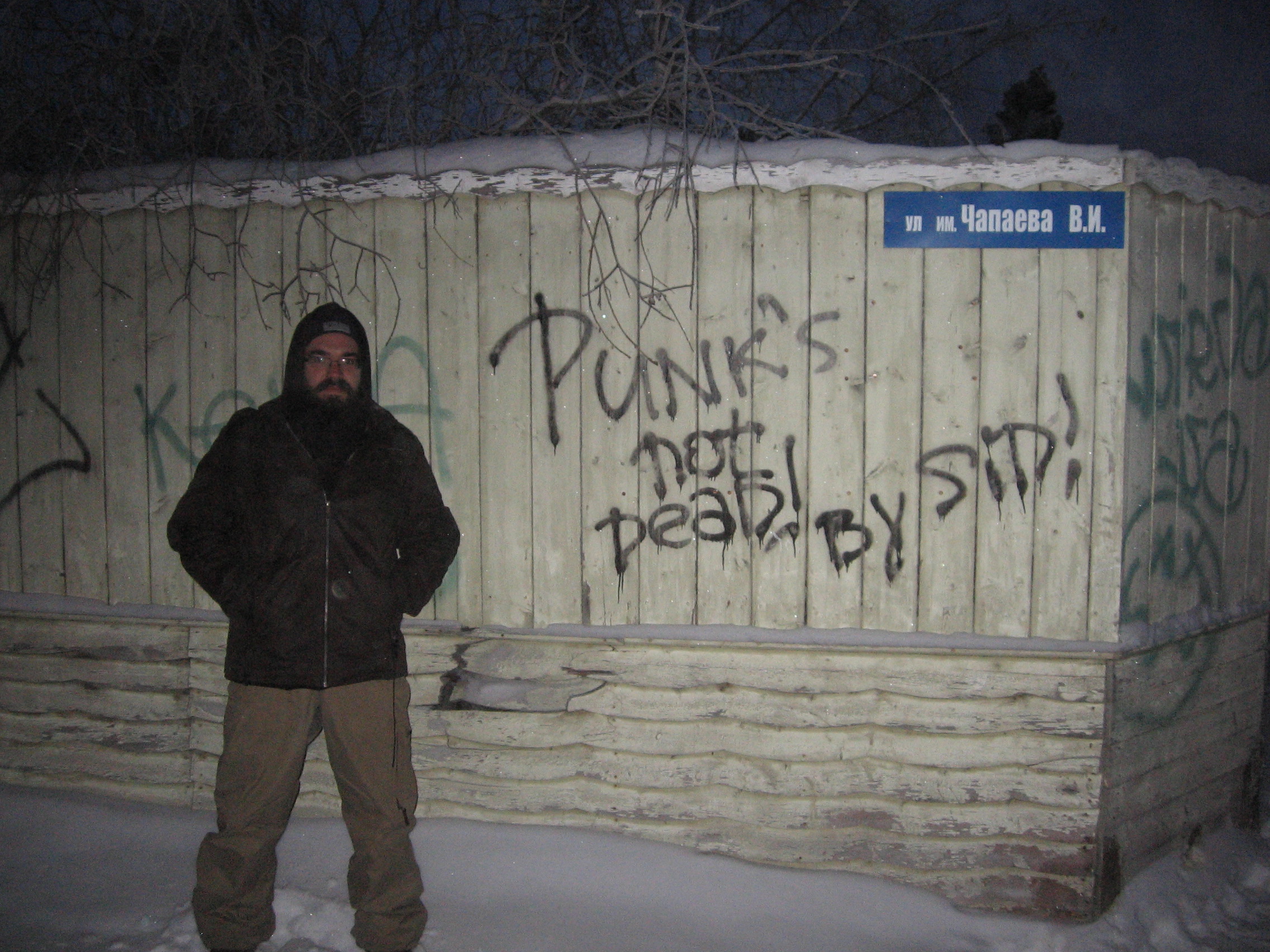

On our way there my friend Krisztián Almási saw a ’Punk's not dead’ sign on the wall and wanted to get out to take a photo of it. They told him the’d get him back there later on but in the meantime they started thinking: ’what did this Hungarian guy see in our town that was so exciting for him’ so they called the regional cultural secretary and took Krisztián to the place in a van that had rooftop flashing lights. So the official guy got out of the car and took my friend’s photo so as to document the event. This seemingly absurd story shows how very important learning is for them. For example they send many students to Rome, Paris and such places in order to see the world and learn because they know that education is the only way out for them. They learn all the time and we learnt an awful lot from them as well. We learnt how very open people can be in such a closed environment while we in the middle of Central Europe are more and more reserved.

When did you decide to make an album from this?

On our way home, basically, on the aeroplane. We saw that it worked and we agreed that we could get invited to other places like Kazakstan, Japan or Iceland for example. Our music is partly instrumental and it does not require thorough knowledge of the given culture, not to mention that the dances can be easily thaught and learnt as well.

How did you choose the name Zoord?

We were thinking hard for a year and when we went to Yakutia they started calling us Madjayar which means something like: the nomadic man from the North who when getting off their horse walk with bow-legs. Of course it’s quite clear that such a name in Hungary would be utterly absurd hence my dad recommended calling it Zord but there was a band called that already so we mutually agreed on calling our band Zoord.

How is the music of Zoord different from other traditional musicians’ repertoire?

We do not wish to play traditional folk music from Moldva. Béla Drabant, our violinist who also plays the drums and the zither and he has another band called Flótás, has been listening to this kind of music since his childhood, he has been to Moldva several times. He reckons it does not make too much sense to just play the music we collect in a place but it is more exciting if we play it in our style. Here in Kecskemét we organise traditional folk dance events every week that are very popular with Erasmus students, rockers and all sorts of people. They have nothing to do with the folk dance movement but are typical urban people who have came across this type of music at our gigs so this how they like it.

Our drummer: Krisztián has listened to punk rock music all his life, he’s mostly into non-mainstream stuff. He has an incredible collection of weird music too. The grooves he plays have nothing to do with traditional folk dance music, nevertheless it perfectly suits the music Zoord plays. So it was pretty obvious what kind of music we should play. All the others were very keen on the cool and rough sound of the Mouth harp so we didn’t even think of having a bass guitarist, we wanted to keep it rough and tough. It wasn’t very difficult to put together the songs – there came a theme and we all went along with that and that was it. The final sound is the work of an old Polish friend: Rafael Kołaciński who mixed the songs and gave us feedback on where to cut it shorter or be more stern. He saw clearly what we wanted and helped us construct the backbone of the album which we took to Yakutia with us.

Our concerts are equally enjoyable as the album and we also have a few new songs. We don’t change much about the structure when we play live. Playing a trio is perfect as chemistry is great, you don’t have to divide your attention that much and you can just go with the flow of music. We move an awful lot on stage which is also quite important in communicating our music. At concerts we don’t ask for a folk band sound but we demand the maximum strength from each instrument. We don’t play nice music. We strike hard and hit the audience.

You have already toured with the album abroad and maybe a little in Hungary too, how did the audience like it?

My network capital concentrates around foreign festival and concert organisers. We have just came back from Japan where we gave many concerts in different places like the Music Academy and a number of small clubs. After the first part of the gig the audience grabbed the gist of what it was all about. Although the Japanese audience is extremely open minded they are not the same as people in the South of France for example. Our music is on the fringe there too. Most of the people who came to our concerts were either interested in Hungarian music or in the Mouth harp. For example on our last day, just four hours before our airplane took off we gave a concert in Japan in front of 200 people. There was such a great, kickass vibe we could hardly stop playing, eventually all the people from the audience stood in line next to our bus and waved us farewell as we left for the airport. We have also been to Kazakhstan where we played at a reception and we gave a lecture at the Music Academy.

You played together in another band: Recyclo some time ago. What happened there?

It was a one-off band, it doesn’t exist any more. The founder of Leskowsky Hangszergyűjtemény (Leskowsky Musical Instrument Collection), Leó (Albert Leskowsky) did not only collect music but also made instruments himself. When I took over the management of the collection in 2009 I realised that there were a great many pieces made of tin and bycicle spoke so I figured we should do something with them too.

Back then I was involved in an environmental programme here in Kecskemét so I suggested organising a street performance. The rhythm was provided by the sour cabbage barrel but there was also a bicyclephone (made of spokes and toilet chains), a tin funnel, train springs, and wind instruments made of drain pipes. We made this just for fun but people really liked it and started calling us for gigs. This was an awfully inefficient venture as it took four hours to unpack and the same length of time to put away all the stuff and we could only play like 20 minutes as it was so unbearable to listen to these instruments on the long run. Some of these instruments are still on display in the collection.

You are invited to workshops all around the world What are they about?

Whenever we are invited to a foreign festival there is usually demand not only for the concert but also for a so called stage programme as well, and that is Mouth harp teaching. Sometimes I’m invited only to teach. At such occasions I try to figure out the level of the audience’s knowledge and show them different playing techniques at a very practical course. I always do my best to sneak in a good Moldva tune and try to teach them such music and tunes that come from my culture. I also show my special technique which is basically about how to play this instrument loudly and leave behind the stereotype that this is just a cute little folk device that adds some flavour to the rest of the band. The task is to convince them that with this instrument one can make an impact on the audience and can make others happy with its sound even in front of thousands of people without making a fool of themselves.

How did you become the manager of Leskowsky Musical Instrument Collection?

I first visited the exhibition when I was two years old when, according to my dad, I pulled the drum kit over myself. Leo, seeing this said: ’oh, there goes my successor’. That is how it really began, but eventually I started volunteering for the collection as a tour guide in 2006.

How did Albert Leskowsky create the collection?

He founded the collection when he came back from Germany where he studied in 1979. He was loaded with excellent books on music and special instruments and he started to investigate the countryside’s farms to meet old zither players and other musical instrument makers. These people, seeing how humbly and respectfully Leo approached them gave away their instruments to him. He was given a small room in the local museum and that is how it began. He was given more and more instruments so the collection grew and of course he also made some weird instruments himself as well. When I took over the institution the main concept was to organise school programmes. In the meantime I started to include workshops and concerts and lately organising festivals too. I believe that musical instruments not only introduce us to music and sounds but also to the culture and habits of another region. Kecskemét is a medium sized city where open minded people who share the same interest can regularly get together to celebrate music and funny musical instruments and this is really fantastic as my aim was to introduce the world of music to everybody.

Once you said that you are mostly interested in music that is testing the limits and as I see most of the bands you invite to the festivals play such music too. What amuses you in the fringes?

Well, there are a lot of bands that play authentic music and I think there’s already plenty of opportunity for bands to go public out there as this style has been around for many decades already. I have always been more drawn to the less well-trodden paths, perhaps it’s a thing that runs in the family. When we first set up our band Navrang in 1999 I wanted to know how I could use the musical instruments in order not to reproduce the same old sounds and style in a new way. Back then, before 2000 it was a unique venture in Hungary to use electronic music - computers and authentic sound at the same time. We used to listen to Transglobal Underground and were truly amazed at how exciting this musical scene was at the time.

I have always been inspired by openness and being affected by more kinds of cultural and musical impacts. The bigger the mix is, the wider the horizon will be. It is particularly interesting if one is affected by so many things during one single concert.

The people dabbling with peripheral ideas will soon find each other. Those people come to our festivals who cannot find enough interesting programmes at mainstream cultural events that would suit their liking. There are many such people out there apparently, not only in Kecskemét but in Budapest, Holland and Macedonia too.

in Hungarian →

A cikk megjelenését az NKA Halmos Béla Program Ideiglenes Kollégium támogatta.

A bejegyzés trackback címe:

Kommentek:

A hozzászólások a vonatkozó jogszabályok értelmében felhasználói tartalomnak minősülnek, értük a szolgáltatás technikai üzemeltetője semmilyen felelősséget nem vállal, azokat nem ellenőrzi. Kifogás esetén forduljon a blog szerkesztőjéhez. Részletek a Felhasználási feltételekben és az adatvédelmi tájékoztatóban.